Kathryn Bigelow’s box office flop celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2020 and it seems time for a reappraisal. It’s still messy and at times crass, but its energy and pace are impressive, the action scenes are thrilling, and its themes of female empowerment and racial oppression resonate with today’s concerns.

Strange Days stars Ralph Fiennes, Juliette Lewis, Angela Bassett and Tom Sizemore, and was produced and written by James Cameron. However, when it was first released, Kathryn Bigelow’s turn-of-the-century sci-fi action thriller made only $8 million compared to its $42 million budget and marked the end of the first phase of her career. After her beguiling debut The Loveless, she made her mark with a trio of action movies: the inventive vampire flick Near Dark, policier Blue Steel and the thrilling surfer/heist movie Point Break.

Strange Days, her entry in the dystopian sci-fi genre, incorporates her flair for high-octane action and breakneck pace that once again masked – or at least allowed us to forgive – the clumsy dialogue and thin characterisations in all these films. But somehow Strange Days was considered a disaster.

It marked the start of a commercial low period for Bigelow that would last a full seventeen years before the surprise hit of The Hurt Locker in 2009, the film that earned her both Best Picture and Best Director at the Oscars and reignited her career. In between, she’d make a couple of terrible films: The Weight of Water, a muddled attempt at mystery-thriller, and the Cold War submarine bore K19: The Widowmaker.

I remember enjoying an early UK preview screening of The Hurt Locker, long before any talk of Oscars. Despite the actual attendance of both Kathryn Bigelow and co-writer Mark Boal at the event, it was held in a tiny cinema and I remember thinking how low her reputation must have sunk. It was Strange Days that began her commercial descent, but its poor reputation is undeserved.

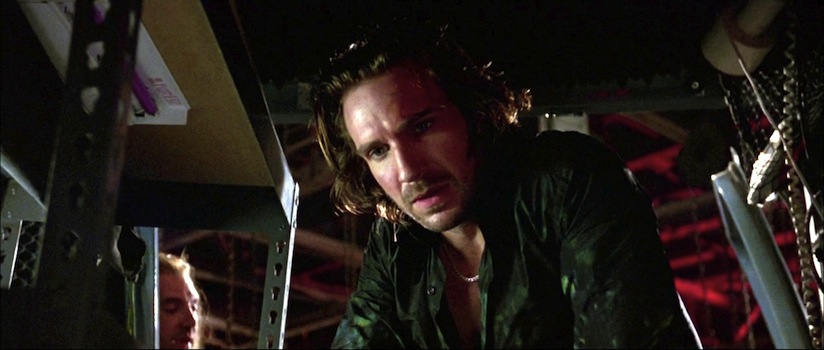

The film is set in a futuristic L.A. warzone over the two days leading up to the turn of the millennium. Fiennes plays Lenny Nero, an ex-cop turned black marketeer who deals in illicit ‘recordings’ of real live events that are replayed directly into the viewers cerebral cortex, to give the cheap-thrill sensation of really being there; a new way to consume pornography and violence. Lenny is obsessed with Faith (Juliette Lewis), an ex-girlfriend who is now with local crime kingpin and impresario Philo Gant (Michael Wincott). When Lenny discovers that someone is trying to kill his friend Iris, he and his friends Mace (Angela Bassett) and Max (Tom Sizemore) are lured into a dangerous setup involving the criminal underworld and corrupt police.

On the whole, the film holds up very well. Like many 1980s and 90s action films it’s over the top and a bit silly in places, but its sheer verve and momentum hold our attention. Fiennes gives us a winning performance as the low-level black-market chancer, relying more on his wit and charm than any sense of threat. It’s a refreshing change of role for the actor who otherwise was known for worthy films such as Schindler’s List and Quiz Show and would soon star in Antony Minghella’s prestige The English Patient. It gives him an opportunity to (quite literally) let his hair down; it’s an enjoyable performance.

Juliette Lewis also commands a lot of the attention in Strange Days and Bigelow’s camera loves her. Lewis had been on a remarkable roll at the time, building a successful career playing dangerously sexual young women and exuding a forbidden promiscuity. She was electric in her breakthrough role as a coquettish yet innocent teen opposite Robert De Niro in Scorsese’s Cape Fear, fascinating as a beguiling temptress in Woody Allen’s exceptional Husbands and Wives, and was captivatingly over-the-top in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers. In almost all these early roles she would capitalise on her wild sexuality, and Bigelow amplifies this.

Had Strange Days been directed by a man, particularly if made today, some of Lewis’s scenes of gratuitous titillating nudity or sexual writhing might have prompted accusations of sexism, particularly as seen through the ‘male gaze’ of Fiennes’s character. But these were different times, and then so-called ‘third wave’ feminism celebrated female sexualisation and promiscuity as empowering if it was done on the woman’s own terms, something that Bigelow tries to capture in this film. Although the script barely allows her to be much more than a trophy, she holds power as the unattainable object of Lenny’s desires, and his rival Philo Gant gets status by having her as his girlfriend. She’s also a grunge singer in Gant’s nightclub, and sways and screams PJ Harvey covers into the microphone in the thrall of her audience (nineties rock band Skunk Anansi also makes a brief appearance). She’s the centre of attention. Interestingly, this is a foretaste of Lewis’s own post-rehab second career as a hard rock singer. Nevertheless, her character does feel reductive, not least because the screenplay gives her character very little agency, and Lewis herself struggles with the admittedly terrible dialogue.

Angela Bassett is much more effective as Mace, a professional driver and bodyguard and Lenny’s friend. Ideally the screenplay should have established her character earlier in the film, but once she’s established she’s a good balance for Fiennes’s Lenny, she acts while Lenny talks, is capable and in control in contrast to Lenny’s chaos. She often comes to his rescue in a refreshing reversal of the norm. Most importantly she’s the moral centre to the film in an amoral universe, expressing her disdain of the pseudo-pornography that Lenny deals in and displaying a strong sense of social morality. Although she has an unrequited love for Lenny, she’s not defined by it. In contrast to Juliette Lewis’s character, here’s a role with real agency and competency, and it reminded me of Geena Davis’s character in the following year’s The Long Kiss Goodnight.

Bassett was presumably cast deliberately as a powerful black woman, embodying one of the film’s other themes: race. Police racism and murder of black suspects is central to Strange Days. The city is on edge after the mysterious murder of a popular black rapper called Jeriko One, an adopted spokesman for disenfranchised and impoverished blacks and who advocates armed resistance against an oppressive society. When Lenny and Mace uncover evidence that implicates the police in the rapper’s murder, it’s Mace who insists that the footage must be shown regardless of the risk of further civil unrest, determined that change is vital.

Strange Days resonates vividly when viewed in 2020 – George Floyd’s filmed death and the consequent Black Lives Matter protests and unrest seem to be uncannily predicted by the 1995 film. Of course, the film was shot a couple of years after L.A.’s Rodney King race riots, and it’s these events that fed into the script; it’s a sad reminder that policy brutality and racism doesn’t seem to have changed at all in the US.

Bigelow would go on to explore that subject with more nuance and anger in her superb and underseen Detroit. However, Strange Days doesn’t really grasp the theme with much sophistication. Sure, it gives us a strong black female protagonist and exposes police racial violence, but from today’s perspective the film feels clumsy and lacks nuance when it seems to valorise unquestioningly the prospect of violent civil unrest as a primary objective.

A Strange Days remade in 2020 would likely favour the perspective that police (and society’s) racism is systemic, while the 1995 film makes it clear that it’s due to just a few bad individuals – the distinction is perhaps a reflection on our changing times and political discourse.

The film’s technology is enjoyably retrograde. The film wisely depicts a future only a few years away, so there’s less scope for howlingly wrong predictions, but it’s still quaint to see mini-discs as the digital storage medium of the future, while in real life that forgotten technology was destined to have a very short shelf-life.

The concept of a recording device that can tap directly into your brain was explored more gently in Wim Wenders’s excellent 1991 film Until The End of the World, which coincidentally was also set in 1999 and with a soundtrack compiled by Graham Revell – that film was even more of a box-office disaster than Strange Days. But Bigelow’s movie is more informed by cyberpunk and in particular William Gibson’s 1980s novels. Cyberpunk would go on to heavily influence films like The Matrix and Existenz in 1999, but in the mid-nineties its reach was mostly contained within the world of sci-fi novels. Strange Days is perhaps an early cinematic adopter (although Johnny Mnemonic, a disastrous Keanu Reeves vehicle loosely based on a William Gibson short story was also released the same year).

The ‘squid’ viewing / recording device that connects directly to the brain recalls the ‘SimStim’ device in William Gibson’s ‘Neuromancer’ and ‘Burning Chrome’ cyberpunk fiction, although the more disturbing concept of a victim watching her own death harks back to Michael Powell’s controversial 1960 film Peeping Tom. In that film the killer forces his female victim to watch her own demise reflected in a mirror mounted on the camera he uses to record the murder. Strange Days updates that by having the victim experience her own rape and murder by having the killer’s perspective connected to her cerebral cortex, literally experiencing her own terror and the killer’s sadistic thrills simultaneously. It’s a very disturbing and dark conceit that is amplified in the film by showing us the lurid footage from the killer’s perspective. It’s to Bigelow’s directorial credit that this depravity doesn’t overwhelm the film’s momentum and energy too much, and the movie remains enjoyable rather than disturbing.

For the film does have an incredible fast-cutting momentum and is always very watchable. There are several impressive action set-pieces, notably the opening scene filmed to give the illusion of a single perspective during a robbery and chase sequence that took a year to plan but is fresh and exciting even today.

It’s also a very crowded film. Perhaps it’s partly because I rewatched it in 2020 when social distancing is the norm, but the sheer kinetic energy of large populated scenes gave the film a real dynamism, whether it’s in the crowds in the nightclub scenes or in the set-piece New Year’s Eve finale which bustles with hundreds of extras in the L.A. streets (a joy denied us in Covid ravished 2020). It seems too that almost every scene is shot in the dark of night, which lends an almost claustrophobic energy and danger.

Admittedly, like many of James Cameron’s films Strange Days is overlong. It tries to cram in too much and might have benefitted from a more efficient script, but it never loses its pace. It also lacks the enjoyably camp tone of Point Break and the film’s few attempts at humour feel a bit forced. But Bigelow never gives us time to reflect on its failings, constantly pulling our attention to the next thrill or spectacle. The plot is ludicrous and the mystery-twist villain is unfortunately very predictable, but there’s so much energy to the film I didn’t really care.

Strange Days is a very enjoyable action thriller, and that enjoyment is perhaps reinforced when rewatched from 2020’s perspective, not least because of its dated tech and social commentary themes. But it’s the film’s relentless energy and spectacle that’s the real draw here and Strange Days still delivers.

Follow @davefilmblogFootnote: the closing credits feature a little known Peter Gabriel song that appears to have reversed vocals! You can listen to it here:

Had been meaning to come back to this. Strange Days seems to not offer the kind of action I wanted at the time; I’ve meant to return to it since. But what puts me off is that I found the POV work and the threat towards women to be problematic at the time, and my guess is that issue will be even more tricky now. Yet the themes are ahead of their time, and reading this made me feel I should watch again; are accusations of exploitation non-valid against female directors? Hmm…

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are two POV scenes that still felt grimy and exploitative and leave a sour taste. I also found the repeated shots of Juliette Lewis either nude or scantily clad misplaced too. Although the director was female, the scenes are intended to be seen through a male character’s eyes in both cases – so I suppose we have a male gaze interpreted by a female gaze. It’s only the women characters who are subjected to such prurience and exploitation. So the end product does feel exploitative, regardless of the sex of the director. I was trying to see the film through the eyes of the time it was made, when the then-current wave of feminism supported the idea that women should celebrate their sexuality to take back power. I couldn’t quite decide if that’s what Bigelow was intending with Lewis’s character, but if it was then I think she failed because although she holds power over Fiennes who is obsessed over her, ultimately the character is still defined (and owned) by men. Interestingly, Bassett’s character isn’t subjected to any of the sexual exploitation that the film seems to indulge in for other female characters. I found it interesting to revisit the film and I enjoyed it more than I anticipated, and while I couldn’t ignore the more exploitative elements, they didn’t spoil the film for me on balance.

LikeLike