Will Orson Welles ever be forgotten? It seems a ridiculous question. Citizen Kane has topped critics best-of lists for decades and surely most people know his name. But then again Vertigo knocked Kane off the top spot in the most recent Sight & Sound poll, and I expect fewer and fewer normal people (i.e. those not obsessed with film) might have seen an Orson Welles movie nowadays.

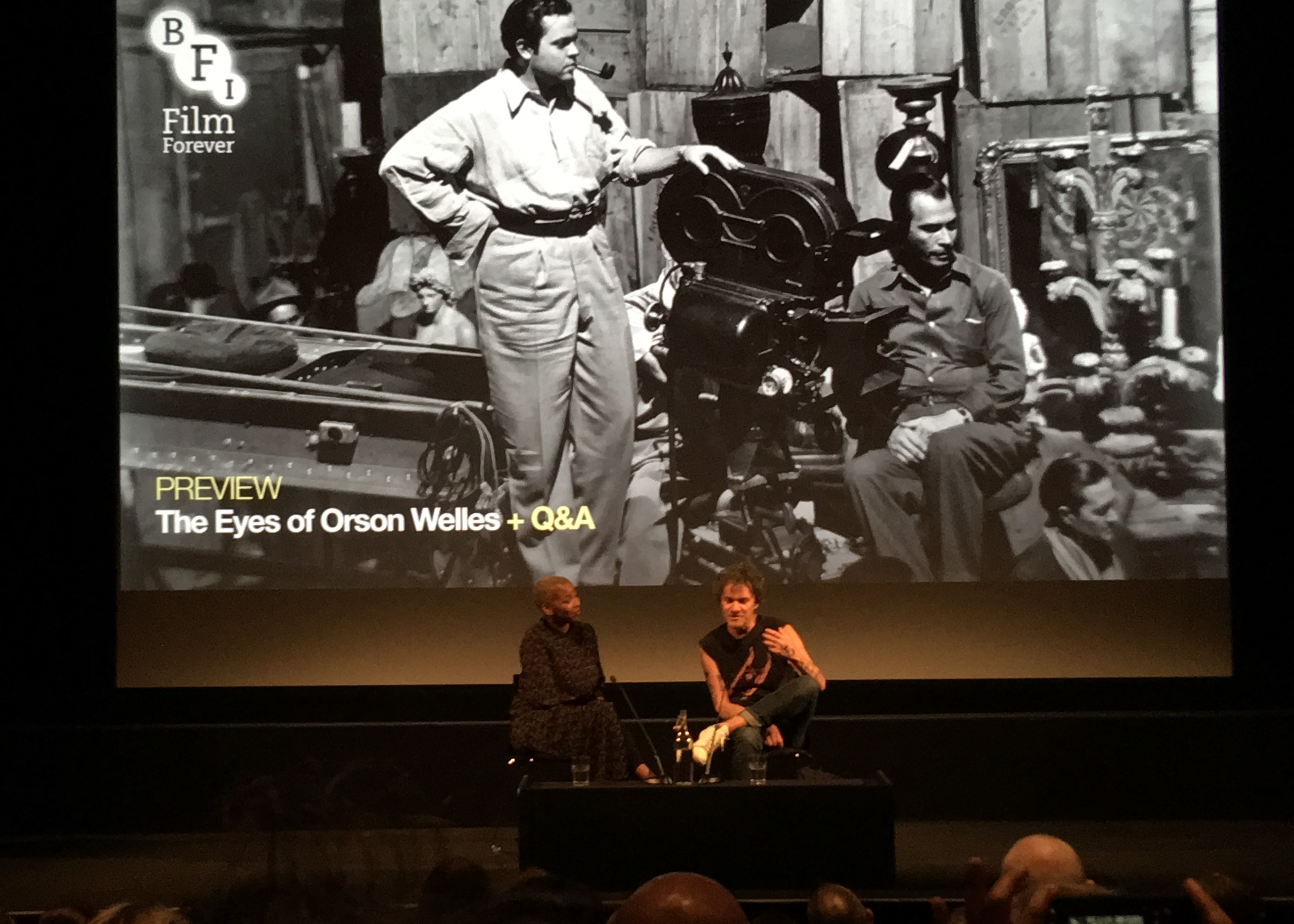

Welles’s third daughter Beatrice seems to fear her father might vanish into obscurity and irrelevance, and she claims this is one reason she became the catalyst behind this fascinating new documentary by Mark Cousins. Admittedly, I suspect she has a further motive – she’s selling some of her father’s paintings including many featured in this film – but whatever the reasons this is a great gift to cinephiles.

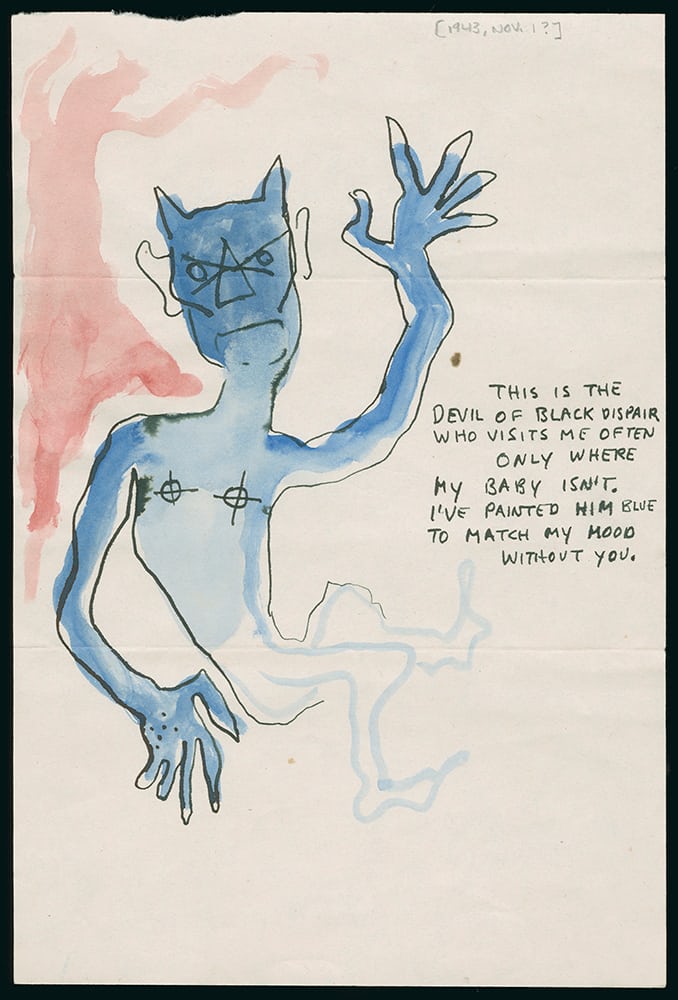

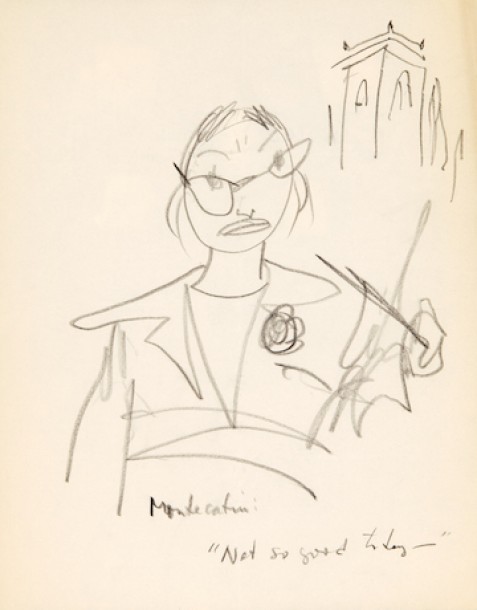

The film is centered on a box of Welles’s paintings, sketches, and letters that has been held in storage in New York for decades. Beatrice has agreed to lend them to Cousins to explore. At the start of the film, we see him recover the box, fly back to the UK (the box gets its own seat in the plane) and the moment when he opens the box at home to discover its contents.

Cousins’s film contemplates how the paintings and sketches might illustrate aspects of Welles’s life and personality, taking the form of a letter from Cousins to Welles, read aloud as voiceover (a common Cousins conceit).

This documentary – or perhaps more accurately, this film essay – is split into chapters. The first, entitled ‘pawn’, considers the everyday people who influenced Welles. This section is mostly biographical, setting context and exploring Welles’s prodigious childhood, his travels to Ireland, first forays in theatre, before moving through aspects of his cinema. We see Welles’s social conscience, taking on cases of injustice, perhaps influenced by his mother.

The subsequent sections are less chronological: ‘knight’ explores his chivalrous side, hopelessly out of time like his Don Quixote, and also his relationships including with Rita Hayworth. This section also explores his guilt and dependence and is perhaps the most complex chapter. In ‘king’ we consider how he is always in charge, in control, dominant, echoed by his portrayals of flawed and complex powerful figures such as Kane, Quinlan in Touch of Evil, MacBeth, and Harry Lime in The Third Man, perhaps his most famous creation.

The final section, ‘jester’ has a slightly different tone. We hear Welles voice, as portrayed by actor Jack Klaff, in response to Cousin’s letter. Klaff is an actor and academic, who had a small role as an X-wing pilot in the original Star Wars: A New Hope and also in the Bond movie You Only Live Twice. He ably mimics Welles’s unique voice. Here we learn about Welles the comedian, the satirist, who doesn’t take things as serious as we first assume. This is Welles as Falstaff, perhaps the most personal of his screen and stage characters.

Mark Cousins is an ideal filmmaker for this project. Welles has a famously distinctive voice, of course, and so does Cousins. His soft, lilting calm narrative sets a contemplative mood. Most importantly he has a strong appreciation for visuals – his latest book is called The Story of Looking – and he is a filmmaker who happens to write about film, rather than a film critic who has never practiced the craft.

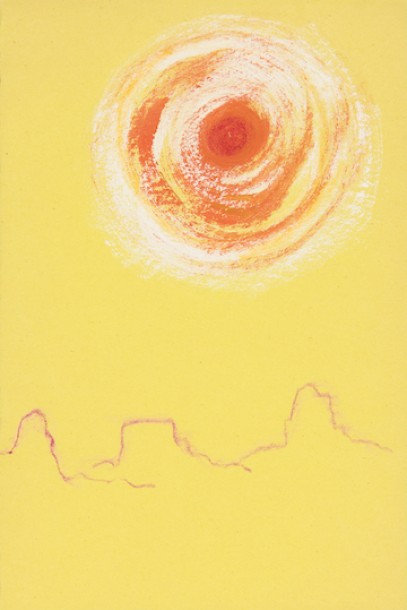

Cousin’s own camerawork is beautifully composed; I was reminded of Wim Wenders eye for capturing meaning in images of the ordinary. He discovers a depth and relevance to Welles’s paintings. What do they depict of Welles’s mood and character? What do they reflect of his soul?

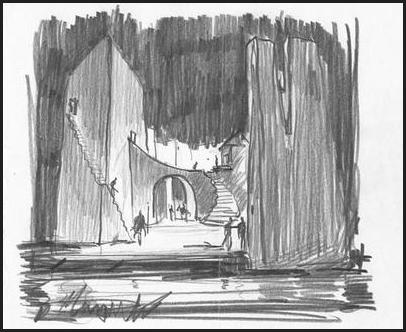

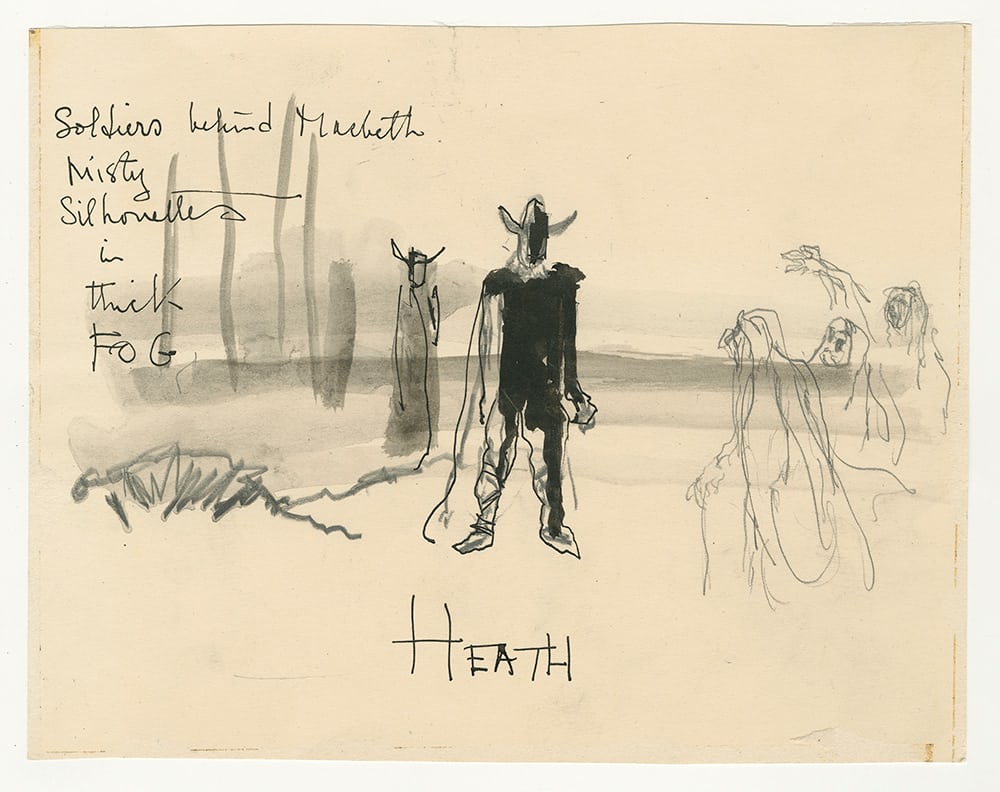

The images are often animated, as if we are watching Welles’s invisible hand creating the image before us, to the sound of a pencil scratching on paper. This isn’t just a gimmick. It makes the images seem more immediate, and it also reminds us that Welles was drawing constantly and these images would have been created rapidly. And the movement is important, echoing the camera movement or eye movement in his movies.

Cousins voiceover is in the present tense, and it’s written in a way that sounds like he’s thinking aloud. In the Q&A he noted that this is deliberate; he didn’t want to sound academic and detached and certainly not authoritative. He wanted the audience to take this journey with him, rather than to feel lectured to. Interestingly, much of Cousins script was written directly in response to the visuals, to keep the images to the fore.

The film is also a rumination on the passing of time. At the start and end in particular, he reflects on what has changed since Welles’s lifetime. Cousins writes his letter to the past, confident that Welles would find new technology fascinating, and ponders with a little melancholy how buildings and theatres that were important to Welles have since vanished or changed.

This is a film for Welles fans, who have seen some of his films and know a bit about the man. It isn’t really a primer for newcomers. Of all his major film works, it barely touches on his most famous films, such as Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons or The Third Man, and instead draws extensively on less well-known films like The Lady From Shanghai, The Trial and in particular his Shakespeare adaptations Othello, Macbeth, and Chimes at Midnight. This could be due partly to Cousin’s distrust of ‘canon’, but in my view these films even with their occasional flaws are just as fascinating and revealing as the official masterpieces.

Mark Cousins is clearly an Orson Welles fan. At the preview screening he enthusiastically showed us his ‘Rosebud’ t-shirt, his Orson Welles tattoo and even a single boot once owned by Welles that he once bought off ebay (the other boot is currently in the Summerhall gallery in Edinburgh where many of the paintings in the film are on display). His excitement and fascination with Welles and these paintings is palpable, and it’s this thoughtful enthusiasm that drives the film. He had clearly read a lot about Welles in the past, and at the Q&A he said he took the opportunity to read those few books he hadn’t yet consumed.

I have seen many of the films that Welles directed and I’ve also enjoyed Simon Callow’s magnificent biographies, so I came to the film with some knowledge. This made the film a richer experience. That said, Cousins was keen to stress that he didn’t want The Eyes of Orson Welles to be another factual documentary. There are plenty of authoritative and comprehensive books and documentaries on Welles. It would be pointless to just make another one.

The Eyes of Orson Welles encourages fans to see the films with a fresh perspective. Cousins said that when making this film, he rediscovered Macbeth. He had previously dismissed that film as a minor work, but his opinion changed after he rewatched it after looking at Welles’s charcoal sketches for the film, and now he considers it amongst Welles’s best. Watching this documentary, I saw a lot of Welles’s creations in a new light.

2018 looks like a fascinating year for Welles fans. His long-anticipated The Other Side of the Wind will be shown for the first time ever at the 2018 Venice film festival, together with Morgan Neville’s companion documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead. Both films will then stream on Netflix from 2nd November 2018. The Eyes of Orson Welles serves as a welcome appetiser before that main event, and it’s clear that despite his daughter’s fears, Orson Welles doesn’t look like vanishing anytime soon.

The website for The Eyes of Orson Welles is here. I found the images from the websites of the Goldenstein Gallery in Sedona and the Guardian.

Update 14th January 2019: A new book of Orson Welles’s art will be published by Titan Books on 19th February 2019, called Orson Welles Portfolio:Sketches and Drawings from the Welles Estate by Simon Braund.

Follow @davefilmblog

I guess one day in the far flung future, Welles will be forgotten but I think we are a long way away from that. Look at all the commotion with the release of his completed final film,

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment – I suspect you’re right. The Other Side of the Wind got a lot of publicity and its presence on Netflix gives it the potential to be seen by a huge audience. Of course, that meant it only got a minuscule tokenistic cinema release, but that’s another discussion (I was lucky to get to see it on the big screen). So, perhaps he won’t be so quickly forgotten as I suspected when I wrote that piece.

LikeLike